Originally written on 19 March 2022 for the Castalia House Blog.

Saturday, April 9, 2022

Wednesday, March 23, 2022

The Red Peril

“Race, you’re one in a million of your kind–and I guess that I am one in a million of mine. Come! I’ll give you a name as feared as yours. They call me ‘The Red Peril’.”

I just gasped up at her. This slip of a girl, the most notorious woman burglar the underworld has ever produced!

Race Williams returns, fresh off of bouts against the Klan and blackmailers. This time, an unsavory man throws $1,000 at him to not take a certain young woman’s case–to find lost diamonds. Instead, Race takes the case to spite the scumbag.

For Miss Muriel Barton needs those diamonds to receive her inheritance–an inheritance soon to be spent to find her missing half sister, Nellie Coleman. By accepting her case, Race Williams finds himself unraveling a web of intrigue and blackmail keeping the half sisters apart. And when he follows a lead to the diamonds, he crosses the path of a masked burglar who has her own interest in the case.

The Red Peril.

If Williams’s previous adventure, “The Knights of the Open Palm”, represented the first popular outing of the hard-boiled detective, Carrol John Daly’s “The Red Peril” is an early example of weird menace, seasoned with the same anti-heroic thread running from Raffles, Lupin, and Fantomas to the Shadow and beyond. And complete with the ropes and the whip. The tale and the lashwork might not be as sensationalistic or as spicy as that seen by an indignant Congress 20 years later, but the slope from here is slippery.

But said slope also illustrates that the ingredients that would create the hero pulps and superhero comics were percolating for years before a certain radio refrain of “The Shadow knows” prompted the emergency creation of a pulp hero. Also, that these ingredients were stewing in contemporary mystery and not just the historical romances like Zorro. And the result, at least at this stage, is another masked cat burglar in the same line as Catwoman and Fujiko Mine. A capable foil and openly romantic interest for a detective of action. And sometimes intimidatingly so.

The pace of the story is rapid, with at least three whipsaw revelations that change everything that Race Williams has previously learned before plunging him into one final life-or-death confrontation. And although Williams is a bit of a self-acknowledged braggart, his skills with his fist and his firearms carry him through situations where mere wits enough are not sufficient. It is satisfying to watch as Williams finds himself out of his depth, only to bluff and intimidate his way back into commanding his surroundings.

Compared to the bloodless puzzles of the Gold Age of Detective stories, Race Williams and “The Red Peril” are earthy, sensationalistic, and bloody. A constant drip of adrenaline, and, occasionally, fear. A short read, to be sure, but one crammed full of plot and excitement, with little time to rest.

Tuesday, March 15, 2022

Saturday, March 5, 2022

Monday, February 21, 2022

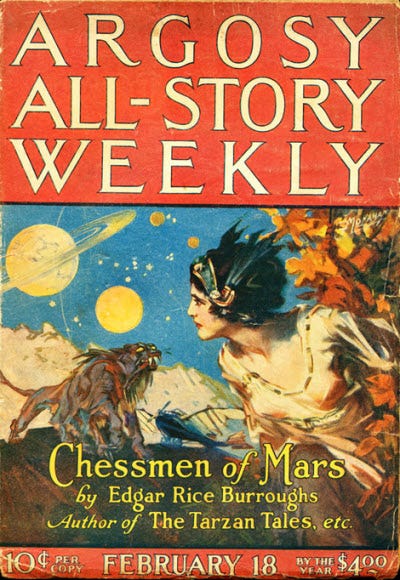

Argosy: The Father of Pulp Fiction

Originally written for the Bizarchives on 13 February 2022.

Tarzan.

John Carter.

Zorro.

Any magazine that published all three of these pulp, nay, American icons would be assured of its place in literary history. But Argosy is much more than that. Argosy is the first pulp fiction magazine, and by far one of the most prestigious of its time. With a run lasting from 1882 to 1978, Argosy set the standard for the entire field. While a general adventure magazine, Argosy dabbled in a little bit of everything, from the fantastic, science fiction, historical fiction, Westerns, war stories, and more. And whenever a genre grew popular in Argosy, some enterprising individual, such as Hugo Gernsback, would create a new genre pulp line to try to cash in its success.

Pulp fans tend to focus on the time between 1894 and 1942 as Argosy’s golden age. Prior to that time, Argosy focused mostly on children’s adventures. Soon, it faced the problem all children’s magazines faced: what happens when your audience grows too old for your stories. So Argosy retooled for a new audience: adults. And to compete, it developed a new format: the pulp magazine, printed on cheap paper.

Circulation quickly skyrocketed until in 1906, it reached a circulation of half a million copies per issue. By comparison, The Shadow at its height cleared 300,000, Amazing at science fiction’s all-time high, only 200,000, Weird Tales and Astounding averaged at 50,000, and today’s science fiction and fantasy magazines, only 5,000 per issue. Argosy’s success inspired a sister magazine, All-Story Weekly, with which it would later merge in 1920. Argosy would be sold to Popular Publications in 1942, which would spell the end of Argosy’s pulp focus, as it would begin to drift into men’s adventure before ending as an almost softcore magazine in the 1970s.

Argosy represents a merger of four magazines: the original Argosy, All-Story Weekly, Cavalier, and Railroad Man’s Magazine. The name changed often to reflect these mergers, but whether Golden Argosy, Argosy All-Story Weekly or Argosy and Railroad Man’s Magazine, the name always drifted back to Argosy. And because of the wide focus on various adventure genres, Argosy later gave birth to Famous Fantastic Mysteries, a magazine devoted to reprinting the best science fiction and fantasy stories found in Argosy. Famous Fantastic Mysteries would sit in science fiction’s Big Three throughout the 1940s alongside Astounding, Unknown, and Thrilling Wonder Stories.

But enough about history. Let’s get to the stories.

Edgar Rice Burroughs and his creations Tarzan and John Carter/Barsoom need little introduction among pulp fans. But if you are interested in strange tales in even stranger places, these stories would be the first place to start. Barsoom, alongside Ralph Milne Farley’s “The Radio Menace”, Otis Adelbert Kline’s “The Swordsman of Mars”, and Abraham Merritt’s “The Moon Pool”, represent mainstream pulp science fiction, and were the stories that inspired the creation of Amazing and later Astounding, magazines devoted solely to science fiction.

Historical adventures abounded in the pages of Argosy. The aforementioned Zorro, for one. But pulp master Max Brand, better known for his Westerns, filled Argosy with Renaissance, Musketeer, and Colonial era swordsmen such as “Clovelly”, Tizzo the Firebrand, and John Hampton, “The American” in the middle of the French Revolution. And the Three Musketeers found their match in Murray Montgomery’s rakehelly adventurers and Richelieu’s swordsmen, Cleve and d’Entreville. And back in the days of Alfred the Great, Phillip Ketchum’s “Bretwalda” would return to save England from the viking menace.

Fans of the weird would find much in Argosy to enjoy. J. U. Giesy and Junius B. Smith would popularize the occult investigator with their stories of Semi-Dual, a strange son of Persia who would solve mysteries “by dual solutions: one material, for material minds; the other occult, for those who cared to sense a deeper something back of the philosophic lessons interwoven in the narrative.” And zombie stories abounded throughout, with Theodore Roscoe penning “Z is for Zombie”, “A Grave Must be Deep”, and many other Haitian zombie stories.

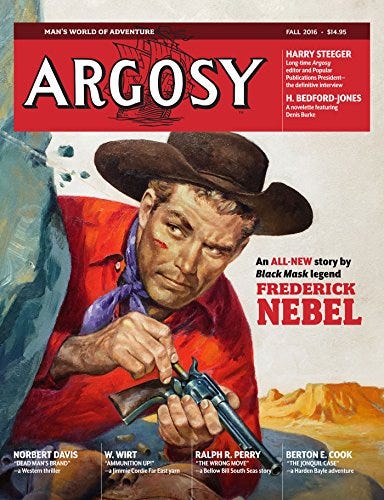

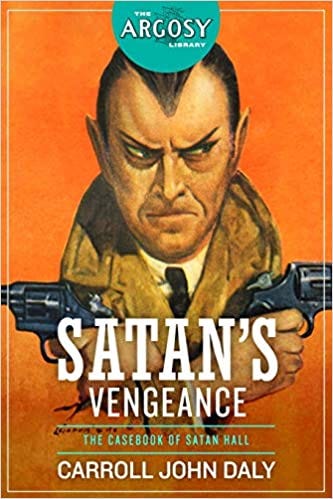

Mystery fans delighted to stories by Carroll John Daly, father of the hardboiled detective genre, including those of Satan Hall, “the cop who believes in killing criminals as they kill others.” W. C. Tuttle’s Sheriff Henry dabbled on the comedic side, as a comedic actor inherits a Western ranch—and the role of sheriff. And Norbert Davis penned his tales of sleuth Doan and his canine partner Carstairs.

Contemporary adventures abounded. Theodore Roscoe tapped into the popular French Foreign Legion genre with Thibaut Corday. Doc Savage author Lester Dent would pen a pair of comedic adventures, including “Genius Jones”. W. Wirt would raise a battalion of black WWI veterans to accompany Captain Norcross into China in “War Lord of Many Swordsmen”. Loring Brent’s radioman Peter the Brazen sailed through various intrigues in the Pacific and China.

If there is one common element tying these stories together, it is how easily most of these tales disappeared from publication, often for decades at a time. But, thanks to recent efforts, many of these once popular series are being offered once more to readers through imprints like the Argosy Library and Cirsova Classics. And although a recent attempt to revive Argosy as a quarterly fell through, there are more undiscovered gems and current writers of adventure waiting for pulp fans to find.

Sunday, February 13, 2022

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Sailor's Grudge

Robert E. Howard is best known for his sword and sorcery tales, and his heroes Conan and Krull. But Howard wrote more stories of Sailor Stevie Costigan than any other of his heroes with the exception of Conan. Costigan was a sailor in the Pacific, hot-headed, quick with his hands, and the fiercest boxer on the seas. Accompanied by his bulldog Mike, Costigan moves from port to port and ring to ring, avenging slights and proving naysayers wrong. Unfortunately, this means that Costigan takes lumps that a few moments’ hesitation may have prevented, something the old salt good-naturedly admits.

In “Sailor’s Grudge”. Steve Costigan’s troubles start where most sailors’ do, on shore, and this time in California. A chance meeting with a little blonde flirt named Marjory puts Steve’s heart into a flutter. When he finds a man named Bert browbeating Marjory for fancying a sailor, Costigan enrages. Not only will no man get between Costigan and his current fancy, Steve pegs the man as a fellow sailor. The ensuing grudge will take Costigan into Hollywood, where he assaults a Bert lookalike that turns out to be a famous actor, one to whom Bert is a stunt double in a boxing movie. Costigan muscles his way onto set, aiming to settle his grudge in the ring, recorded by the movie’s director. But will this production have a happy ending?

Not when Steve learns the real connection between Marjory and Bert.

Costigan retells this misadventure knowing that the joke is on him, and that this white knight was tilting at windmills of his own devising. Howard nails the voice convincingly and appropriately for a lighter tale than the Gothic-tinged fantasy he is better known for. Better yet, he does it subtlely, using a few choice words here and there instead of the thick and occasionally unreadable accents many of his contemporaries used in the name of “realism”. The result is a quick, even friendly read that speeds the reader along to the highlight–the fight.

The fighting is painted in broad strokes. Technical, as an experienced boxer might, but with an eye towards how the fight fits in Steve’s attempts at courtship. Verisimilitude is the name of the game. Just enough boxing jargon to preserve Costigan’s expertise in the ring, but not so much that it turns into the Dreaded Checklist of Action or to stall the story’s narration. The punches mentioned move the story forward, not to wallow in technique, and each punch moves Steve closer to the realization that he doesn’t have a puncher’s chance with Marjory.

While Conan and Solomon Kane are classics of the fantasy genre, Costigan’s voice and the approachable nature of his adventures make his tales my current favorite of Howard’s works.

Sunday, May 9, 2021

The Cosmic Courtship

Love at first sight turns into a love that transcends the cosmos in Julian Hawthorne’s lost pulp romance, The Cosmic Courtship. 1917’s Argosy saw the introduction of Jack Paladin, nephew of a famous explorer, and his attempt to win the hand of the brilliant Miriam Mayne. But when Miriam goes missing, Jack sets out to find her. Even if that means beaming himself to the ringed world of Saturn to retrieve her from a sorcerous space tyrant. The result is a strange, redemptively Christian mix of romance and raygun romance that presages C. S. Lewis’s better-known Out of the Silent Planet. But where Lewis’s Ransom tries desperately to prevent another fall, Paladin and his Saturnian allies seek to redeem and restore those who are lost.

Editor P. Alexander, who is bringing The Cosmic Courtship back into print, describes Hawthorne’s background:

While most are at least somewhat familiar with Nathaniel Hawthorne as one of the great American authors, less well known is that his son, Julian Hawthorne, was an incredibly prolific writer in his own right. Julian wrote on a wide variety of subjects, ranging from literary analysis of his father’s works to poetry to period romances and adventures. Late in his career, Julian even dabbled in the emerging genre of Science Fiction [Hugo Gernsback had only recently coined the awkward term “Scientifiction” when this story was first published.]

It is hard not to compare Hawthorne’s interplanetary adventures to those later adventures of the Inklings. The prose is elevated and aspirational, ornate without being purple, and a far cry from the simplifications of the Black Mask style to be born ten years later. Hawthorne sets out to explore love, both romantic and compassionate, and places it in an otherworldly realm that cleaves closer to fairy tales than the unimaginative sciences of Hugo Gernsback. It becomes difficult to not draw parallels between The Cosmic Courtship and Lewis’s Malacandra and Tolkien’s Samwise Gamgee, as examples of an unfallen Christian cosmic kingdom and steadfast, sacrificial friendship have fallen out of favor.

Hawthorne’s tale of a love-spanning worlds is among the brightest of the noblebright stories, highly aspirational and pure in motive and archetype, unmarred by baser desire or concern. Mirrors are common throughout the tale, as is fitting, since Hawthorne uses the reflections in his story to present what each of us should be. Paladin is brave, disciplined, decisive, and committed to his love. Miriam is beautiful, clever, and unwavering in her devotion, even when worlds are promised to her by her captor. Paladin’s crippled servant Jim may be unsophisticated, but his loyalty is absolute and pushes him to braveries beyond those of his master’s. And the Saturnians are just yet tempered by mercy, ever seeking to restore those lost to their passions and desires to the One from Whom all love flows.

Hawthorne’s imagination also is unbound by the later conventions of fantasy. While the high prose and the aspirational heroes only add to the fairy tale nature, the strange creatures, clothes woven from actual fire, lost civilizations, and angels visiting unaware add to the palpable sense of wonder shining from the tale. In many ways, The Cosmic Courtship is the fulfillment of Jeffro Johnson’s assertion of the essentially Christian roots of fantasy.

Fortunately, The Cosmic Courtship has been recovered from obscurity by Cirsova Publishing. A wildly successful Kickstarter is in its final days, with a wider public release to follow. This success ensures not only that The Cosmic Courtship will be available to wider audiences once again, but that the rest of Julian Hawthorne’s pulp romances will join it.

Thanks to Cirsova Publishing for the advance copy.

Thursday, June 18, 2020

The Curse of the Golden Skull

How strange it seemed, that he, Rotath of the Moonstone and the Asphodel, sorcerer and magician, should be gasping out his breath on the marble floor, a victim to that most material of threats -- keen pointed sword in a sinewy hand.Rotath spends his dying moment cursing the gods that allowed him to die. As their dark servants come for him, this sorcerer casts one last desperate and spiteful spell that changes his body, one that he hopes will wreak havoc across the ages.

In the "Emerald Interlude", the ages pass:

Years stretched into centuries, centuries became ages. The green oceans rose and wrote an epic poem in emerald and the rhythm thereof was terrible. Thrones toppled and silver trumpets fell silent forever. The races of men passed as smoke drifts from the breast of a summer. The roaring jade green seas engulfed the lands and all mountains sank, even the highest mountain of Lemuria.That's the entire interlude, a descriptive section filled with as much tumult and cataclysmic action as can be fit into 64 words. And, in its way, it's emblematic of the entire "The Curse of the Golden Skull". Howard comes out swinging with his descriptions and fills the story with the struggle of the fight. The Jeffro Johnson test for covers (have people busy with action instead of standing around looking cool) applies here. And this is just the contemplative section denoting that the time is passing.

The final section, "The Orchids of Death", picks up with an unnamed adventurer discovering the skull and skeleton of gold:

What long dead artisan had shaped the thing with such incredible skill? He bent closer, noting the rounded ball-and-socket of the joints, the slight depressions on flat surfaces where muscles had been attached. And he started as the stupendous truth was borne upon him.The adventurer, of course, is doomed. But is it from the curse or from natural causes? Like most short stories of the era, it all hinges on a twist at the end, a terrible denouement that alters everything that has come before.

The sections and the uneven lengths obscure the dramatic structure present. The first line immediately thrusts a problem upon Rotath. 600 words in, almost the exact center of the story, Rotath attempts his spiteful defiance, the turning point for the story. And in the last lines, we learn whether or not his dying action succeeded. This follows the conventional five-act dramatic structure, albeit with an abbreviated introduction and denouement, and without acts. And Howard's conflict-filled prose is well suited for drama, even if ages fly past in mere lines.

"The Curse of the Golden Skull" was a happy little discovery nestled deep in the lines of a search engine. As such, it is a delightfully harrowing read that rewards the critical eye's scrutiny. For, like a good house, the construction is as sound as the facade is beautiful.

Friday, June 12, 2020

The Avenger, The Lady, and The Wheel

I recently came across another direct pulp inspiration in another media. Inside the pages of Hitchcock, by Francis Truffaut, the famed suspense director Alfred Hitchcock is interviewed about many of the movies in his career. One in particular sounded familiar, 1938's The Lady Vanishes, the film that brought Hollywood's attention to Hitchcock. From Wikipedia:

"The film is about a beautiful English tourist travelling by train in continental Europe who discovers that her elderly travelling companion seems to have disappeared from the train. After her fellow passengers deny ever having seen the elderly lady, the young woman is helped by a young musicologist, the two proceeding to search the train for clues to the old lady's disappearance."Swap the train for a plane, the elderly lady for a wife and daughter, the menacing spy ring for the mob, and the young woman for a Doc Savage style adventurer, and you have the origin story for 1939's The Avenger, as Richard Henry Benson's adventures begin when his wife and daughter vanished mid-flight from the seats next to his. Everyone thinks Benson is insane, with a brain flu that tells him he has family not his own. The shock turning Benson's skin and hair a steel gray is a unique touch though.

Hitchcock's movie is drawn from the 1936 book by Ethel Lina White, The Wheel Spins, but he indicates that there might be an earlier source:

Hitchcock's movie is drawn from the 1936 book by Ethel Lina White, The Wheel Spins, but he indicates that there might be an earlier source:The whole thing started with an ancient yarn about an old lady who travels to Paris with her daughter in 1880. They go to a hotel and there the mother is taken ill. They call a doctor, and after looking her over, he has a private talk with the hotel manager. Then he tells the girl that her mother needs a certain kind of medicine, and they send her to the other end of Paris in a horse-drawn cab. Four hours later she gets back to the hotel and says, “How is my mother?” and the manager says, “What mother? We don’t know you. Who are you?” She says, “My mother’s in room so and so.” They take her up to the room, which is occupied by new lodgers; everything is different, including the furniture and the wallpaper.

It’s supposed to be a true story, and the key to the whole puzzle is that it took place during the great Paris exposition, in the year the Eiffel Tower was completed. Anyway, the women had come from India, and the doctor discovered that the mother had bubonic plague. So it occurred to him that if the news got around, it would drive the crowds who had come for the exposition away from Paris.The criminality and spycraft is distinctly White's addition to the story, and the close parallels to The Wheel Spins and The Lady Vanishes suggest that Lester Dent, Walter Gibson, or Paul Ernst was familiar with either the book or the movie. However, Gibson also drew heavily on French influences for The Shadow, so it would not be a surprise to find out that he drew on the Paris version of the story to help create The Avenger. The real answer might be hidden within the Street & Smith archives.

Tuesday, June 9, 2020

Manly Wade Wellman: A View From 1940

Westerfield also spent a few paragraphs to describe Amazing's top writers. Number one was Eando (Otto) Binder, now best known as Supergirl's creator and the writer of many of Captain Marvel's best adventures. (That's DC's Shazam!, not the much embattled Marvel character.)

Number two, however, was a surprise:

Manly Wade Wellman runs Binder a close second by pounding out some 200,000 words of science fiction a year which amounts to $2,000. Like Binder, Wellman loves science fiction and makes it his specialty. He gets some of his plots from our old-time wild west, revamps the location to that of a savage planet, and presto he has a science fiction yarn. Wellman, a former newspaper reporter, got his first taste of science fiction when he wrote a propaganda story in which he pictured Martians as friends instead of enemies. The yarn brought him such a large letter response that Wellman has been doing pseudo science yarns ever since. He feels that most science fiction writers don't put forth their best efforts and most of their stuff is dine too hurriedly--including some of his own work.It is a bit bizarre to see Wellman treated as a science fiction writer, given that he is now best known for his Weird Tales and John the Balladeer stories. But Wellman was able to earn a year's pay from Amazing alone, one comparable to the many junior scientists and engineers reading science fiction pulps at the time. The eagle-eyed reader will recognize Wellman's science fiction plotting technique as the same the Wellman's friend David Drake uses in the Royal Cinnabar Navy series, although Drake prefers to use classical history instead of the wild west.

Also of interest is Westerfield's hobbyist writers, which includes such notables as E. E. Smith, Abraham Merrit, L. Sprague de Camp, and Ralph Milne Farley. Although hobbyist might be too much a diminishment of these men's second careers. None was reliant on writing for their primary source of income.

It is easy to view with perfect hindsight the authors of the past. Columns like Westerfield's allow a clearer glimpse into what a writer's contemporaries thought at the time, as well as give hints to now forgotten writers of merit.

Tuesday, April 28, 2020

The Call of Adventure

The first issue of Adventure contained 19 stories on 188 pages, but prior to the first story was a message on pages [iii] and [iv]. It is signed The Ridgway Company but may have been written by White or perhaps even by Arthur Sullivant Hoffman, the man who would become his successor; it provides the editorial philosophy of the new magazine:

Have you ever noticed how the recital of an adventure always finds ready audience?

The witness of an accident never wants for listeners, and if peculiar and mysterious circumstances surround the accident, the interest is all the keener. The man with a story of some stirring adventure always gets the floor. Men will stop the most important discussion to listen, women will forget to rock the cradle, boys and girls will neglect any sport or game.

Try it some time and see how it grips all kinds, all ages.

And the reason is that none of us ever really grows up. We are always boys and girls, a little older in years, but the same nature—alert to the new, questioning, investigating, growing, living; stirred by martial music; thrilled by the sight of the fire-horses dashing madly down the street; lured by tales of subtle intrigue and splendid daring.

It will be a sad day for this old world if men and women ever lose this capacity to be gripped by tales of heroism. The man whose heart leaps for joy at sight of a heroic deed is the man who will act the hero when his turn comes.

No, the love of adventure will never be lost out of life. It is a fundamental of human nature, just as sentiment is a fundamental, and it is almost as moving. So we reasoned that a magazine edited for this universal hunger of human nature for adventure ought to have a wide appreciation and appeal, and we decided to publish such a magazine and call it ADVENTURE.

It is published in the hope and belief that hundreds of thousands of men and women will be glad to have a magazine wherein they can satisfy their natural and desirable hunger for adventure.

A magazine wherein they can find adventure without being obliged to read through reams of stuff they care little about for the sake of getting a little they care a lot about. sto

A magazine published by the publishers of Everybody’s Magazine and edited with the same care and concern as is Everybody’s Magazine, but frankly made for the hours when the reader cannot work, or does not wish to, or is too weary to work. Frankly made for the reader’s recreation rather than his creative hours.

If you care for stirring stories (and who does not?) — if you wish to get away for a brief time from the hard grind of the daily mill so that you can come back to it again with new zest, so that you can walk through the knotty problems and nagging limitations with renewed courage — get a copy of Adventure.

You can get away for such a trip every month for 15 cents or you can get a season ticket entitling you to twelve trips for $1.50.

A better mission statement for the writer I've yet to find. For more information on Adventure, (and the source for the quote) see "A History of Adventure" by Richard Bleiler. And thanks to StoryHack Magazine for pointing me to this.No other kind of story in the magazine; just Adventure Stories. Factstories as well as fiction stories. If you don’t like that kind, don’t buy; but if you do like that kind, Adventure is sure to delight you.

Wednesday, April 15, 2020

The Pineys

Nothing but tall tales and campfire scares, right?

Beau Sawtelle believes so, and it is his job to survey the piney grove for logging. He's brought his niece, some men, and a local named Mac to assist him. The local tales of strange and furred creatures don't scare Sawtelle's party, but rather provide a bit of amusement as they journey deep into the forest. But as the canopy darkens overhead and the shadows grow longer, the discussion takes a more fearful turn as they discuss the Pineys' king while they make a campfire...

Some stories just ache to be told out loud, and this last gasp of a Gothic tale, stitched together from campfire recollections and short tales, sounds like the stories told late at night by a storyteller aiming for a little mischief. As mentioned, this is a ghost story, so the impact rests on the final revelation, heightened further by whom the narrator is.

All the hallmarks of a proper Wellman tale are present. Mac's voice is reminiscent of John the Balladeer, who would appear in "O Ugly Bird" a mere three months later. The Pineys themselves fit the inventive bestiary that fills Wellman's tales, and he even draws a distinct parallel to the Shonokins, a race that filled several of his earlier Weird Tales. And finally, Sawtelle's niece relies on the same European folk magic and grimoires that John the Balladeer would use to great effect in his short stories. It's easy to see "The Pineys" as a sinister rehearsal for what would John's adventures, more so that "Frogfather" or "Sin's Doorway". Just call Mac "John..."

"The Pineys" may be a simpler scare than the heyday of Weird Tales under Farnsworth Wright, but atmosphere and voice can make even the simplest tales breathe with sinister life. Fortunately, the most affordable place to find "The Pineys" is in the new reprint of Worse Things Waiting, which is still available through Amazon.

Thursday, April 2, 2020

The Pendulum

Bradbury riffs on the old misunderstood scientist theme and succeeds in making a haunting tale of a man essentially trapped on a giant swing. But what he captures is the shocking arrogance that is too common in the scientist fiction of that day. (See Jack Williamson's "The Iron God" for one example.) Compare the scientists in many of the stories in the 1930s and 1940s, slipshod, power-mad, and quick to experiment on humanity, and quicker to take offense when any sort of accountability is required of them, to the obligation of the engineer:

Monday, March 16, 2020

Coming Soon: The Black Mask Library

The titles will include:

Dead and Done For: The Complete Black Mask Cases of Cellini Smith, by Robert Reeves

Murder Costs Money: The Complete Black Mask Cases of Rex Sackler, by D. L. Champion

Let the Dead Alone: The Complete Black Mask Cases of Luther McGavock, by Merle Constiner

Dead Evidence: The Complete Black Mask Cases of Harrigan, by Ed Lybeck

Boomerang Dice: The Complete Black Mask Cases of Johnny Hi Gear, by Stewart Sterling

Blood on the Curb, by Joseph T. Shaw, editor of Black Mask

While it is uncertain as to how the current unpleasantness may delay these plans, I intend to review at least one of these titles as soon as they are available. Black Mask gave the world the hardboiled detective and, later, film noir, and rightly has its place among the most important pulp magazines. Hopefully, Steeger Books will take a chance and publish stories in some of the other genres Black Mask dabbled in, such as science fiction.

Thursday, February 20, 2020

Better Than Bullets

As for Roscoe, a trip to the Caribbean and North Africa in 1928 and 1929 inspired an interest in old voodoo tales and the French Foreign Legion, both topics he would explore in the pages of Argosy to great acclaim. Per Gerd Pilcher’s introduction to the Better Than Bullets collection, “reading an ordinary pulp story was compared to ‘reading in black and white,’ reading a story by Roscoe however as to ‘reading in technicolor.’” The countless encounters with Legion officer and veterans no doubt fueled the authenticity of Corday’s tales, and covered for the occasional lapse. After all, a good storyteller is concerned more with the appearance of reality.

Like many writers in the Forties, Roscoe would leave the pulp world, this time for the more lucrative true crime tales. Thanks to Altus Press (now Steeger) reprinting Thibaut Corday’s tales, readers can still find the old legionnaire in an Algerian café, waiting to tell his tall tales. And like so many old soldiers, his first tale, “Better Than Bullets”, holds more humor than war:

“You say, my American friends, that bullets are the best of weapons? But yes, perhaps. And with bullets I am a man the most familiar…Splendid for the fight. But—I recall a battle I fought in which I used never a blade or a single bullet…No soldiers ever fought with weapons more strange!”With that, the old legionnaire begins a tale most familiar to any man in uniform—how a little bit of mischief blows up into something far worse, terrifying in the moment, but ridiculous in hindsight. In 1907, Corday's legion just completed a long march on little water and worse food. His partner in crime, a Yankee known as Bill the Elephant, sees farmhouses in the distance, and convinces Corday and Christianity Jensen to join him in a little “foraging expedition” at night.

Their raid finds a pair of piglets and fifteen bottles of wine. As the trio carouses, however, a gang of Moslem dervishes comes across them with murder on their mind and an inclination to linger over the task. Now the trio of legionnaires are trapped red-handed in the farmhouse, with nothing more than bottles, boots, bacon, and beehives to defend themselves. But will these things prove to be better than bullets?

It’s an amusing tale where the ridiculousness of the scenario is played straight, and a classic example of the military definition of serendipity: “yes, we screwed up, but it turned out better than if we hadn’t.” That fact doesn’t save the trio from two weeks of hard labor for breaking their commander’s orders, though, so the story ends in proper military fashion, with the guilty punished and a dash of self-deprecation.

Rather than speak of the Argosy prose style yet again, “Better Than Bullets” is vivid because of Thibaut Corday’s voice. Roscoe expertly captures the flair of a verbal storyteller in Corday’s first-person tale to the point where a reader can almost hear the legionnaire. This is a story that begs to be performed in audio, not read, to recreate the effect of listening to a master of tall tales over a cup of coffee. The descriptions also are vivid and tight within Corday’s voice, with the little descriptive tangents fitting where a café storyteller would naturally make such. No doubt, Roscoe spent time listening to storytellers in addition to reading them.

Monday, February 10, 2020

A Sword for the Cardinal

But ill-advised political poetry might force that question, as Comte Guy d'Entreville soon discovers. For Cardinal Richelieu himself signed the papers sending Guy's love, Catherine, to a convent for smuggling subversive papers.

According to The Argosy Library:

"Much-revered and enjoyed by thousands of Argosy readers, these fast-paced stories have never before been reprinted."That explains the paucity of information about the series, the characters, and their author. But does "A Sword for the Cardinal" live up to the ad copy?

It's a good start. The action is slick, with time and chance playing as big of a part as skill. It pays to be both good and lucky. And, like most pulps, "A Sword for the Cardinal" spends most of its time exploring the consequences of Guy's decision to turn his back on his political "friends" for the sake of his girl. Not all the resulting pyrotechnics are confined to action, either.

Comte Guy d'Entreville fills the same role as D'Artagnan, just for the Cardinal instead of for the King. He's young, foolish, brave, skilled, and proud-and of a higher station than Dumas' hero. But where The Three Musketeers villainizes Cardinal Richelieu, Montgomery portrays the Cardinal as a unifying force in France, clearing away the feudalistic barriers and privileges that leave France open to the machinations of Buckingham, Spain, and others. Although he has changed sides, Guy still fights for France--and his pride.

The highlight of the story is its ending. The Cardinal is saved, but deigns to dismiss Guy from his service. The rebuke to Guy's stiff pride is too much for the noble to bear. It is an insult to Guy to not be considered good enough to serve the Cardinal. His Catherine is freed, therefore he must serve the Cardinal as per their deal. In a roaring display of audacity, Guy forces the Cardinal to accept his service.

Just as planned.

It's the mix of honor, integrity, and pride displayed in such a gesture that sets Guy apart from the procession of historical Argosy heroes. Competency is expected, as always, but there is a flair to all of Montgomery's characters not normally present. But if your heroes are going to pitch musketeers into fountains over questions of honor, style and swagger are required.

On the technical side, "A Sword for the Cardinal" is standard Argosy prose: clear, clean, and still contemporary almost 80 years later. As always, best to have a dictionary or encyclopedia handy. Not only does the text expect a certain familiarity with the historical setting, but a bit of French is also present. And, most pleasantly, this is not Three Musketeers fanfic or pastiche. As for the poetry present, whether Guy's verses are befitting a poet or a poetaster, I'll leave to those more qualified. Although that question is one argued throughout the series, with Guy cooling the heads of his most vocal critics on a regular basis.

But I was promised the misadventures of a pair of rascals in the Cardinal's employ. And for that, we must read on.

Monday, January 6, 2020

Peter the Brazen: "A Princess of Static"

The action is blink-and-miss-it quick, the exoticness of China and Chinatown is subdued compared to the chinoiseries of the late 20s and early 30s, and the less said about the Chinese accented dialogue the better.

Sunday, December 22, 2019

The Shadow: Gangdom's Doom

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

The Sheriff of Tonto Town

"When we first meet Henry Harrison Conroy he's a down-at-the-heels vaudeville comedian who seems to be modeled on W.C. Fields...Just as he learns his stage career is over, he gets a letter saying he's inherited a ranch in Arizona. So to Arizona he goes."

"Along the way, Henry is elected sheriff as a joke, and turns the joke on the town by remaining in office. He knows nothing of the law, and cares less, but somehow - usually with a drink in his hand - manages to bring about some justice."