Originally written for the Bizarchives on 27 February 2022.

Pulp fiction is full of Big Threes, from the top magazines every author wanted to write for, to the top three science fiction writers, the top three science fiction magazines, and the top three Weird Tales writers. But there were three magazines deemed so culturally important that these were the only pulps to go straight from the presses into the archives of the Library of Congress. And while Argosy was the father of the pulps, these three magazines represented the best of the genre pulps, from which countless subgenres of literature, film, and comics originated:

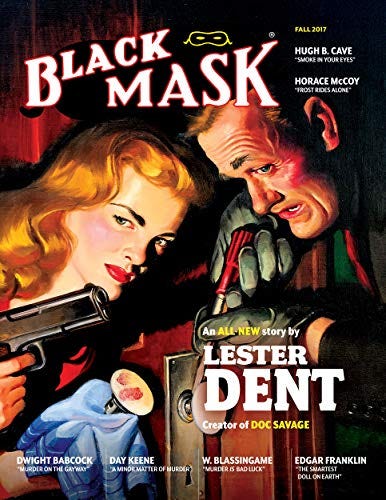

Black Mask

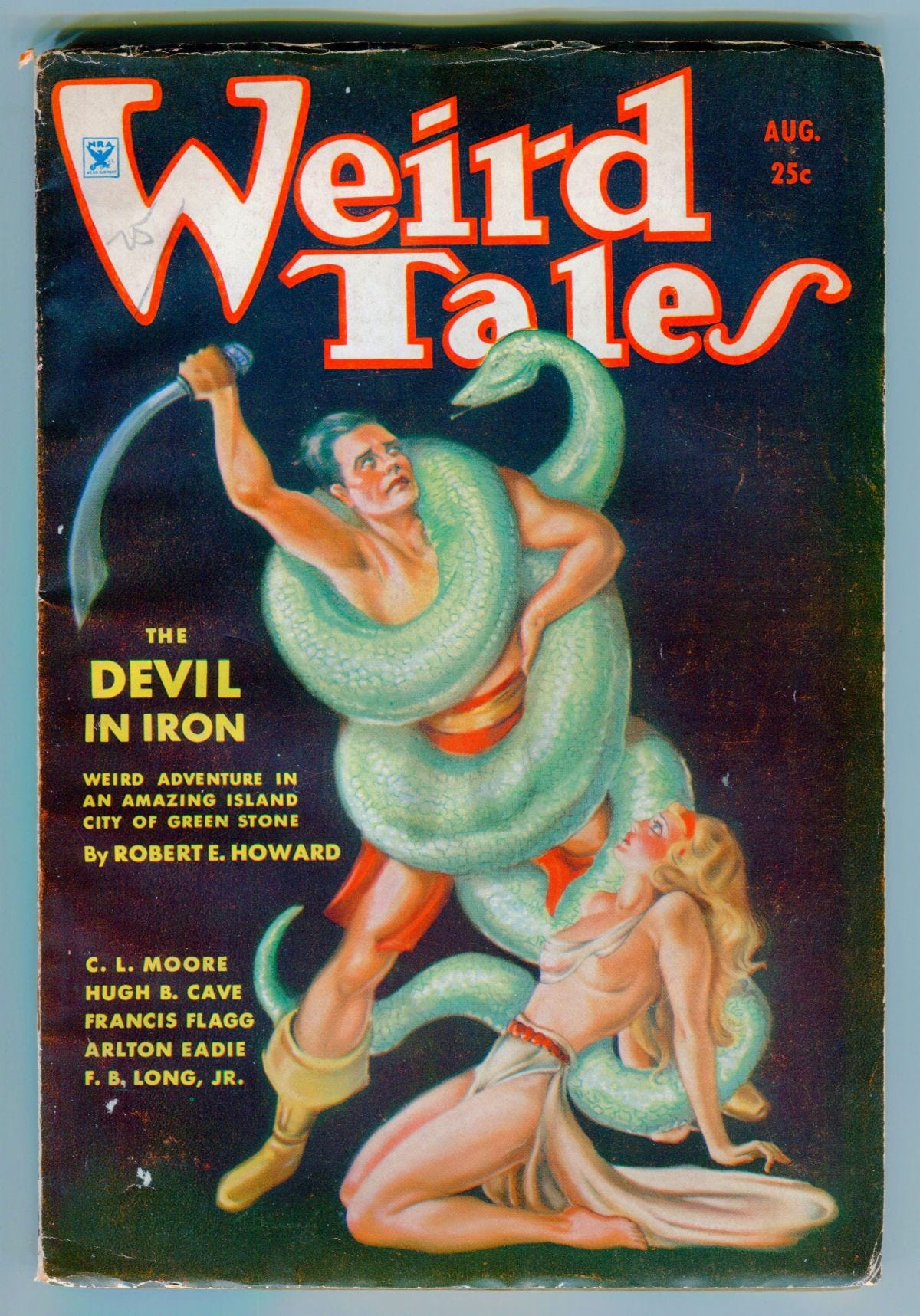

Weird Tales

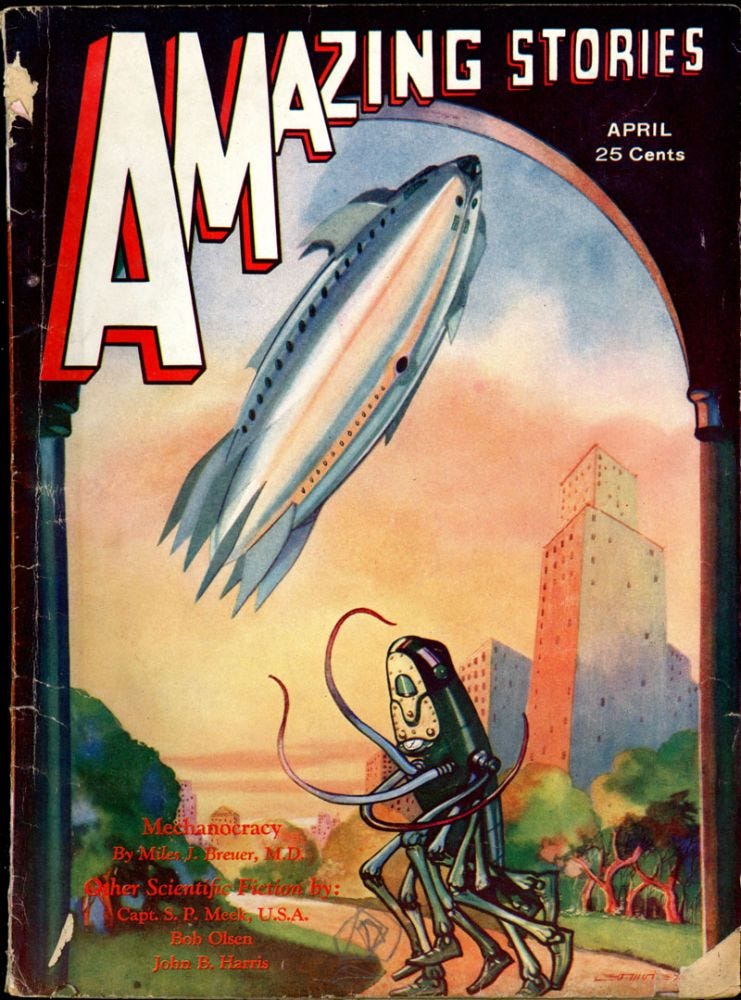

Amazing Stories.

In April 1920, journalist H. L. Mencken created Black Mask as one of many money ventures to support his literary journal. While starting as a general fiction magazine, after Mencken cashed out, Black Mask grew more sensationalistic, bloodier, and more obsessed with crime. And then, in 1923, Black Mask picked a fight with the Klu Klux Klan in a special edition devoted to detectives fighting against the Klan. Foremost among these was Race Williams, the first breakout hard-boiled detective, in “Knights of the Open Palm”. Written by Carrol John Daily, Race Williams was

“…what you might call a middleman – just a halfway house between the cops and the crooks. I do a little honest shooting once in a while – just in the way of business, but I never bumped off a guy who didn’t need it…”

A couple months later, Dashiell Hammet followed up with “Arson Plus”, the first case of the Continental Op. Soon after, under the editorial eye of Philip C. Cody and legendary editor Joseph Shaw, the magazine’s stable would include Raymond Chandler (creator of Philip Marlowe), Erle Stanley Gardner (creator of Perry Mason), Frederick Nebel, Paul Cain (writer of The Fast One), Theodore Tinsley (co-writer for The Shadow), and more. In the process, these writers helped create the masculine and stripped-down writing style mistakenly called the Hemingway style, moved detective stories from the clean puzzles of the Golden Age to something more two-fisted, and inspired the film noir genre, which would employ many of these writers to adapt screenplays of their own works. Weird menace, hero pulps, and comics trace their lineage to these stories as well.

But those wanting something a little bit…unique…would turn to another magazine.

Weird Tales began in 1922, and soon fell under the editorship of the legendary Farnsworth Wright. Billing itself as “The Unique Magazine”, Weird Tales quickly established itself as the premiere magazine for weird fiction, supernatural fiction, and the plain bizarre. Readers may be drawn in by the adventures of occult detective Jules de Grandin, written by Seabury Quinn, only to find R. E. Howard’s hero Krull declaring “By This Axe, I Rule”, then facing off against Cthulhu cultists written by H. P. Lovecraft, before visiting the wild future of Clark Ashton Smith’s “Zothique.” C. L. Moore’s Northwest Smith would inspire a legion of space smugglers to follow, while her Jirel of Joiry would be the first woman to hack her way into sword and sorcery. Manly Wade Wellman would bring his unique and harrowing monsters to scores of morality tales before creating his own occult detective in John Thunstone. Ray Bradbury would find an early home here, writing stories “that weren’t science fiction, but were too wonderful not to be included”. Henry Kuttner, Psycho author Robert Bloch, E. Hoffman Price, Fritz Leiber, “World Wrecker” Edmond Hamilton…the list of Weird Tales alumni is long and distinguished.

As was the cultural spillover. Solomon Kane. Conan. Cthulhu. The legion of Conan and Mythos stories, filling books, comics, and movies attests to the staying power of Weird Tales’ authors. Weird Tales stories quickly found their way into radio dramas and even Twilight Zone episodes on television. Even current shows like South Park and others mine these stories and their sequels for pop culture relevance. Weird Tales might have been the last flowering of the American Gothic tradition, but there is something about the weird, that sincere encounter with the unknown and disturbing, that keeps bringing the imagination back to “The Unique Magazine”.

For those who wanted the stars, there was one more magazine…

As Amazing Stories goes, so goes the health of science fiction. Not only the first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories was once the most popular science fiction magazine, setting circulation records that stand to this day, eighty years later. The history of this venerable science fiction magazine is still being written, but let’s focus on its pulp days—up until 1950.

In 1926, legendary editor Hugo Gernsback’s keen eye saw the popularity of science fiction tales in Argosy, Black Mask, and elsewhere, and decided to make a genre magazine around science stories and science fiction stories. While Gernback’s idea of science fiction stories would also include stories similar to CSI and Mythbusters, the genre would soon coalesce into the raygun romances that the pulps were known for. E. E. Smith’s Skylark spaces operas and Philip Francis Nowlan’s Buck Rogers appeared in the early days, alongside A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool. Isaac Asimov and John Campbell (he of Astounding Stories and The Thing fame) got their start in the pages of Amazing Stories. And 1940s pulp writers included Eando Binder, H. Beam Piper, Fritz Leiber, Clifford Simak, and Frederic Brown.

And then came “I Remember Lemuria”, by Richard S. Shaver. This controversial start to the “Shaver Mysteries” set up a world where every ill affecting humanity could be traced to an subterranean society of robots. Part Hollow Earth, part conspiracy theory, this predecessor to shows like The X-Files resonated with readers, driving Amazing Stories’ circulation to its record heights. At the same time, science fiction fandom raged hard against the Mysteries, even going as far to try to cancel the series multiple times through the Mysteries’ four year run. After a change in editorship, the Mysteries were finally dropped—and so did Amazing Stories’ sales.

The irony here is that fandom dealt the blow to the magazine that created it in the first place. Gernsback was not just marketing science fiction, but science fiction clubs who would drive interest in his magazines and other associated ventures. And so, fandom, science fiction conventions, cosplay, and much of geek culture stem from Gernsback’s fostering of connections between fans through letters and clubs.

Amazing Stories would continue to have an active influence on American pop culture from the 1950s and beyond, serving as an entry point to readers and authors into the genre. But Amazing Stories, like Black Mask and Weird Tales, would illustrate that the foundation to American pop culture is pulp fiction. Just in Amazing Stories’ case, it also created how people interact with pop culture as well. And for that reason, Amazing Stories joined Black Mask and Weird Tales, all three hot off the presses, as immediate additions to the Library of Congress’s archives.

No comments:

Post a Comment