On 20 December, 2022, sword and sorcery scholar Brian Murphy posted a review of Karl Wagner’s Night Winds at Goodman Games. In the middle of this, he expressed hope for a Wagner revival, and dropped an interesting rumor for the hopeful:

On the rumor-ish side, publisher Baen is reportedly laying the groundwork for a long-awaited reprint of the Kane stories. As I understand it, the estate holders have been approached and some tentative agreements are in process. This would be an enormous win for sword-and-sorcery fans, who have been deprived of good, reasonably priced print editions of these wonderful stories for far too long. Today you are limited to what I understand to be poorly edited Kindle editions, very expensive/out of print hardcovers by Centipede Press, or increasingly hard-to-find though still obtainable Warner paperbacks from the 70s/80s.

The Kane series has been on my radar for a while now, as Karl Wagner was close friends with Manly Wade Wellman and David Drake. But, like Wellman’s stories ten years ago, readers have had to luck into the original paperbacks, luck into expensive premium hardcovers, or know someone who knows about quiet reprints. (Like how the ebook of Mountain Magic replaced all of Henry Kuttner’s stories with Manly Wade Wellman’s Who Fears the Devil? because of rights issues. And it’s still the best way to get John the Balladeer stories.)

Fortunately for Wellman fans, DMR Books and Shadowridge Press have been bringing long out-of-print Wellman stories and novels back in affordable ebooks from DMR Books and paperbacks. Perhaps, with these rumors surrounding Baen, it is Karl Wagner’s time to return.

And, with The Hollywood Reporter’s news that Kane has been optioned for TV series and/or movies, now is a perfect time.

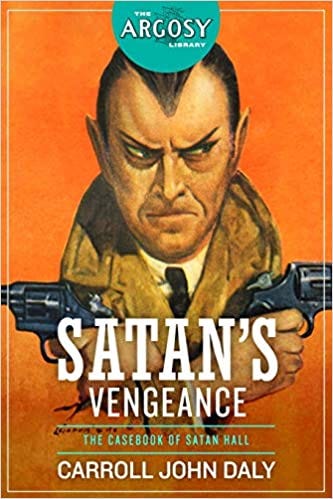

Wagner’s stories, published throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, center on an immortal antihero named simply Kane who is equal parts warrior, sorcerer, marauder and conqueror.

Lee, Trapani and Schneider, who count It, Winchester and the Paranormal Activity movies among their numerous credits, will produce what could end up as a series or feature film. Also on the producing team are Keith Previte and Kevin Elam of the Karl Edward Wagner estate.

First appearing in 1973 and going on to appear in 20 short stories and three novels, Kane falls squarely into the epic fantasy sphere that proved influential to the geek crowd of that time, and 4 million copies have been sold. Famed fantasy painter Frank Frazetta even illustrated several covers.

Fantasy icons Conan the Barbarian and Elric of Melnibone were clear influences, which is not a surprise, as Wagner, on top of being an author, was an editor and a publisher, putting out Conan collections as well as gothic horror and pulp volumes. He died at the age of 48 in 1994.

Kane’s adventures take place in a visceral world steeped in ancient history, with bloody conflicts and dark mysteries. Wagner wove gothic horror elements into this pre-medieval landscape, taking Kane on fantastic sagas involving war, romance, triumph and tragedy.

After retweeting Brian Murphy’s article, suggestions for support emerged from fans.

- Use the hashtag #KaneAtBaen to show visible support.

- Email info@baen.com and ask about Kane reprints. This is also a great opportunity to inquire about other series that could use a little attention. But, please, limit these emails to once a month.

- Support Baen’s upcoming sword and sorcery offerings. For those who wish to try before you but, many of these writers’ short fiction are currently showcased in Tales From The Magician’s Skull, which, although a Goodman Games magazine and not a Baen collection, would give a good introduction for when Baen releases their novels later this year. And, of course, pick up the novels, too.

So, if you’ve read Kane, or, like me, have always been interested in seeing what the hype is about, feel free to show your support so that Baen might bring Kane back.

Days after Perry Rhodan invited the world to join him in the new city of Terrania, the Chinese siege intensifies, even scoring a success by shooting down Rhodan’s only spaceship, the Stardust. In an attempt to get around the Arkonide shields, General Bai Jun cuts off humanitarian aide to refugees flocking to Terrania. But the Chinese government has other ideas, and smuggles nuclear weapons into the Gobi Desert.

Days after Perry Rhodan invited the world to join him in the new city of Terrania, the Chinese siege intensifies, even scoring a success by shooting down Rhodan’s only spaceship, the Stardust. In an attempt to get around the Arkonide shields, General Bai Jun cuts off humanitarian aide to refugees flocking to Terrania. But the Chinese government has other ideas, and smuggles nuclear weapons into the Gobi Desert.