Originally written for the Bizarchives on 13 February 2022.

Tarzan.

John Carter.

Zorro.

Any magazine that published all three of these pulp, nay, American icons would be assured of its place in literary history. But Argosy is much more than that. Argosy is the first pulp fiction magazine, and by far one of the most prestigious of its time. With a run lasting from 1882 to 1978, Argosy set the standard for the entire field. While a general adventure magazine, Argosy dabbled in a little bit of everything, from the fantastic, science fiction, historical fiction, Westerns, war stories, and more. And whenever a genre grew popular in Argosy, some enterprising individual, such as Hugo Gernsback, would create a new genre pulp line to try to cash in its success.

Pulp fans tend to focus on the time between 1894 and 1942 as Argosy’s golden age. Prior to that time, Argosy focused mostly on children’s adventures. Soon, it faced the problem all children’s magazines faced: what happens when your audience grows too old for your stories. So Argosy retooled for a new audience: adults. And to compete, it developed a new format: the pulp magazine, printed on cheap paper.

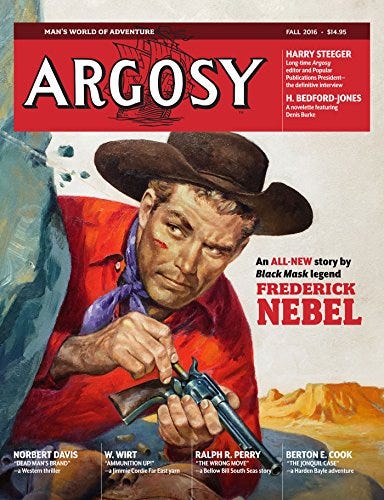

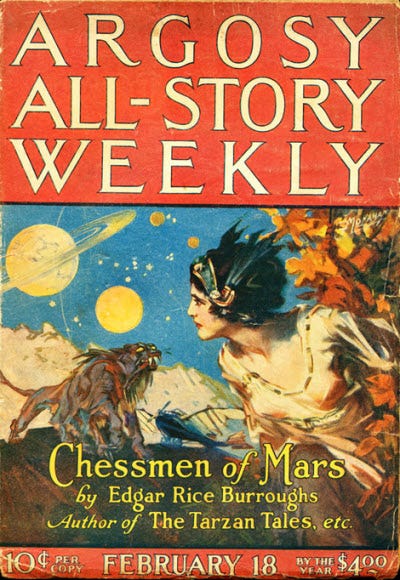

Circulation quickly skyrocketed until in 1906, it reached a circulation of half a million copies per issue. By comparison, The Shadow at its height cleared 300,000, Amazing at science fiction’s all-time high, only 200,000, Weird Tales and Astounding averaged at 50,000, and today’s science fiction and fantasy magazines, only 5,000 per issue. Argosy’s success inspired a sister magazine, All-Story Weekly, with which it would later merge in 1920. Argosy would be sold to Popular Publications in 1942, which would spell the end of Argosy’s pulp focus, as it would begin to drift into men’s adventure before ending as an almost softcore magazine in the 1970s.

Argosy represents a merger of four magazines: the original Argosy, All-Story Weekly, Cavalier, and Railroad Man’s Magazine. The name changed often to reflect these mergers, but whether Golden Argosy, Argosy All-Story Weekly or Argosy and Railroad Man’s Magazine, the name always drifted back to Argosy. And because of the wide focus on various adventure genres, Argosy later gave birth to Famous Fantastic Mysteries, a magazine devoted to reprinting the best science fiction and fantasy stories found in Argosy. Famous Fantastic Mysteries would sit in science fiction’s Big Three throughout the 1940s alongside Astounding, Unknown, and Thrilling Wonder Stories.

But enough about history. Let’s get to the stories.

Edgar Rice Burroughs and his creations Tarzan and John Carter/Barsoom need little introduction among pulp fans. But if you are interested in strange tales in even stranger places, these stories would be the first place to start. Barsoom, alongside Ralph Milne Farley’s “The Radio Menace”, Otis Adelbert Kline’s “The Swordsman of Mars”, and Abraham Merritt’s “The Moon Pool”, represent mainstream pulp science fiction, and were the stories that inspired the creation of Amazing and later Astounding, magazines devoted solely to science fiction.

Historical adventures abounded in the pages of Argosy. The aforementioned Zorro, for one. But pulp master Max Brand, better known for his Westerns, filled Argosy with Renaissance, Musketeer, and Colonial era swordsmen such as “Clovelly”, Tizzo the Firebrand, and John Hampton, “The American” in the middle of the French Revolution. And the Three Musketeers found their match in Murray Montgomery’s rakehelly adventurers and Richelieu’s swordsmen, Cleve and d’Entreville. And back in the days of Alfred the Great, Phillip Ketchum’s “Bretwalda” would return to save England from the viking menace.

Fans of the weird would find much in Argosy to enjoy. J. U. Giesy and Junius B. Smith would popularize the occult investigator with their stories of Semi-Dual, a strange son of Persia who would solve mysteries “by dual solutions: one material, for material minds; the other occult, for those who cared to sense a deeper something back of the philosophic lessons interwoven in the narrative.” And zombie stories abounded throughout, with Theodore Roscoe penning “Z is for Zombie”, “A Grave Must be Deep”, and many other Haitian zombie stories.

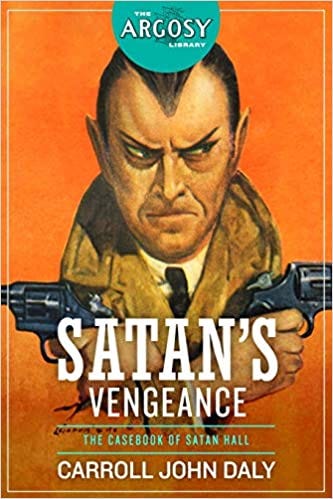

Mystery fans delighted to stories by Carroll John Daly, father of the hardboiled detective genre, including those of Satan Hall, “the cop who believes in killing criminals as they kill others.” W. C. Tuttle’s Sheriff Henry dabbled on the comedic side, as a comedic actor inherits a Western ranch—and the role of sheriff. And Norbert Davis penned his tales of sleuth Doan and his canine partner Carstairs.

Contemporary adventures abounded. Theodore Roscoe tapped into the popular French Foreign Legion genre with Thibaut Corday. Doc Savage author Lester Dent would pen a pair of comedic adventures, including “Genius Jones”. W. Wirt would raise a battalion of black WWI veterans to accompany Captain Norcross into China in “War Lord of Many Swordsmen”. Loring Brent’s radioman Peter the Brazen sailed through various intrigues in the Pacific and China.

If there is one common element tying these stories together, it is how easily most of these tales disappeared from publication, often for decades at a time. But, thanks to recent efforts, many of these once popular series are being offered once more to readers through imprints like the Argosy Library and Cirsova Classics. And although a recent attempt to revive Argosy as a quarterly fell through, there are more undiscovered gems and current writers of adventure waiting for pulp fans to find.

No comments:

Post a Comment